Introduction: The Format Everyone Teaches (And Why They’re Right)

Let’s be honest: the 5-paragraph essay gets a bad rap. It’s called rigid, formulaic, even “the hamburger essay” as a joke. So why has this structure survived for decades in every English classroom across the country?

Because it works.

Think of it not as a cage for your ideas, but as training wheels for your thinking. It’s not the only way to write, and for advanced topics, you’ll outgrow it. But for 90% of school assignments, it’s your most reliable tool to organize thoughts, present a clear argument, and, most importantly, get a good grade without guessing what the teacher wants.

I’ve graded hundreds of essays. The students who struggle are the ones who write in a freeform, messy stream of consciousness. The students who excel? They master this structure first. Once you own it, you can bend it, adapt it, and even break it effectively.

Today, I’ll show you the exact anatomy of a 5-paragraph essay, walk you through a full example, and explain why internalizing this format is the fastest way to build writing confidence.

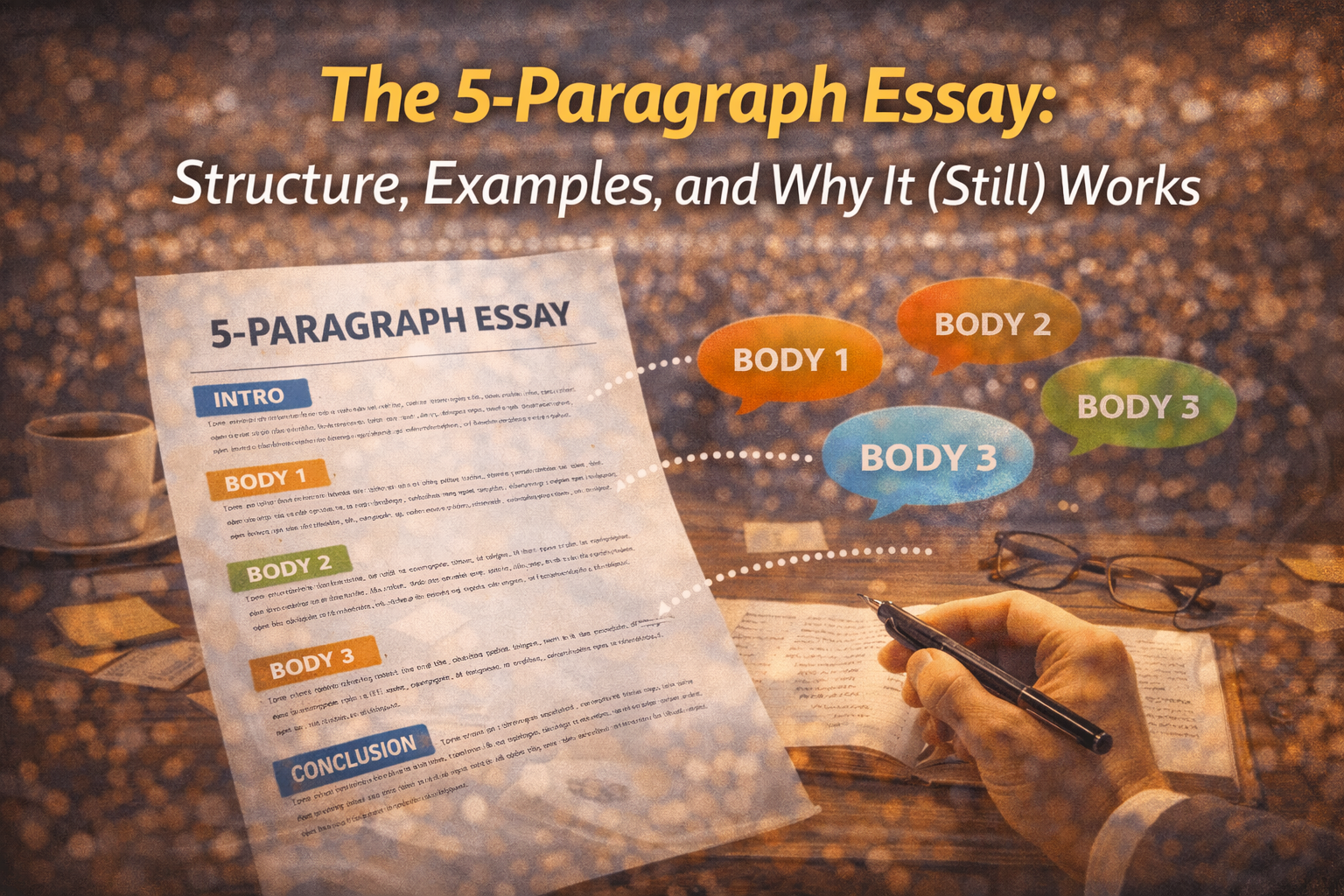

Part 1: The Anatomy of a 5-Paragraph Essay

Let’s break down the blueprint. This structure is all about creating a clear, logical journey for your reader.

Paragraph 1: The Introduction

Your introduction has one job: to funnel your reader from a general idea to your specific, arguable point.

- The Hook: Grab attention. (1-2 sentences)

- Ask a question: “What if a single invention could connect billions, spread knowledge, and yet also fuel anxiety and division?”

- Use a surprising fact: “The average teenager spends over seven hours a day on screens, much of it on social platforms.”

- The Bridge/Context: Narrow the focus from your hook to your topic. (2-3 sentences)

- Briefly introduce the subject—in this case, social media.

- The Thesis Statement: This is the heart of your entire essay. It’s one clear sentence that states your position and previews your three main points. (1 sentence)

- Formula: “[Your argument] because of [Point 1], [Point 2], and [Point 3].”

- Example: “While social media platforms offer valuable connection, their net impact on teenagers is negative due to their effects on mental health, sleep patterns, and real-world social skills.”

Paragraphs 2, 3, & 4: The Body Paragraphs

Each body paragraph is a mini-essay dedicated to proving one part of your thesis. They should follow the T.E.E.A. structure:

- Topic Sentence: Clearly states which of your three points this paragraph will cover.

- Example (for Point 1): “Firstly, social media usage is directly linked to increased rates of anxiety and depression among teens.”

- Explanation/Elaboration: Explain what you mean in more detail.

- Evidence: Provide proof. This can be a statistic, a quote from an expert, a study finding, or a logical example.

- Example: “A 2022 study by the American Psychological Association found that teens who spent more than 3 hours daily on social media were twice as likely to report poor mental health outcomes.”

- Analysis: This is the most important part! Don’t just drop a fact and run. Explain how and why this evidence proves your topic sentence.

- Example: “This correlation suggests that the constant comparison to curated, idealized lives creates a pervasive sense of inadequacy and FOMO (fear of missing out), eroding a teenager’s natural self-esteem.”

- Anchor/Transition Sentence: Link your analysis back to the main thesis and/or transition to the next point.

- Example: “Thus, the very platforms designed to connect us are, ironically, fostering a generation that feels more isolated and insecure.”

(Repeat this T.E.E.A. structure for Body Paragraphs 3 and 4, covering your other two points.)

Paragraph 5: The Conclusion

Your conclusion is not just a summary. It’s your final chance to drive your argument home.

- Restate the Thesis (in new words): Don’t copy-paste. Show you’ve proven it.

- Example: “The evidence clearly shows that the drawbacks of social media for teenagers—mental health decline, sleep disruption, and stunted interpersonal development—outweigh its benefits.”

- Summarize Main Points: Briefly recap your three arguments, but synthesize them. Show how they worked together.

- Example: “From psychological harm and physical fatigue to the degradation of face-to-face communication skills, the costs are pervasive.”

- The “So What?” / Clincher: Leave the reader with a final, memorable thought. This could be a call to action, a broader implication, or a look to the future.

- Example (Call to Action): “It is therefore imperative for parents, educators, and policymakers to advocate for digital literacy and healthier online boundaries to protect the well-being of young users.”

- Example (Broader Implication): “Ultimately, the question isn’t whether we can log off, but whether we can reclaim the authenticity of human connection in a digitally saturated world.”

Part 2: A Complete 5-Paragraph Essay Example

Topic: Is homework beneficial for students?

(Introduction)

For decades, homework has been a staple of education, a nightly ritual of worksheets and textbook readings. However, its true value is increasingly being called into question. While traditionally viewed as essential for reinforcement and discipline, the growing body of research suggests that the burdens of homework often outweigh its academic benefits. Excessive homework assignments can negatively impact students by reducing crucial family time, increasing stress levels, and failing to reliably improve academic performance.

(Body Paragraph 1 – Point: Reduces Family Time)

The first major downside of homework is its encroachment on valuable family and personal time. After spending seven or more hours in school, students are sent home with the equivalent of a second shift. This leaves little room for activities that are vital for holistic development, such as shared family meals, extracurricular hobbies, or unstructured play. A study from Stanford University found that 56% of students considered homework a primary source of stress, directly cutting into time for family interactions and relaxation. When every evening is consumed by assignments, the opportunity for family bonding and personal growth diminishes, teaching students that productivity is more important than personal relationships or well-being. Therefore, the cost of this “reinforcement” is the erosion of a balanced childhood.

(Body Paragraph 2 – Point: Increases Stress)

Furthermore, heavy homework loads contribute significantly to unhealthy stress and anxiety in students. The pressure to complete large volumes of work perfectly, often across multiple subjects, can be overwhelming, especially for older students. This chronic academic pressure is linked to sleep deprivation, headaches, and even symptoms of burnout. Pediatricians have reported a rise in school-related stress complaints, directly tied to homework demands. This analysis reveals that homework is not merely challenging—it can be a direct threat to student health. The anxiety it produces can create a negative association with learning itself, undermining the very goal of education.

(Body Paragraph 3 – Point: Fails to Improve Performance)

Finally, the fundamental argument for homework—that it boosts academic achievement—is not strongly supported by evidence, particularly for younger students. Renowned education researcher Harris Cooper has found that the correlation between homework and standardized test scores is minimal in elementary school and only moderately positive in high school. For many subjects, the quality of in-class instruction and engagement is far more impactful than repetitive take-home tasks. This suggests that hours of mandatory homework are an inefficient use of a student’s time if the goal is genuine learning and mastery. The persistence of heavy homework, then, seems based more on tradition than on proven results.

(Conclusion)

In light of the evidence, it is clear that the conventional homework model requires serious reconsideration. The practice too often steals family time, heightens stress, and provides questionable academic returns. The cumulative effect is a generation of students who may be overworked, anxious, and disenchanted with learning. Moving forward, educators should prioritize meaningful, quality classwork and explore alternative, less intrusive forms of skill reinforcement that protect students’ well-being and their right to a life outside of school. The goal of education should be to cultivate lifelong learners, not merely efficient homework completers.

Part 3: Why This “Simple” Format is a Secret Weapon

- It Forces Clarity of Thought: You can’t hide a messy argument in this structure. It demands one clear thesis and three distinct supports. This is the essence of critical thinking.

- It Teaches Discipline: Like a musician practicing scales, this format builds the fundamental muscle of organizing ideas before you write. This discipline makes longer, more complex essays much easier later.

- It’s a Universal Safe Bet: When you’re unsure what a teacher expects, this format is almost always correct. It demonstrates you understand the basics of argumentation.

- It’s a Springboard, Not a Cage: Once you master it, you learn where to adapt. Need four body paragraphs? Add one. Want to put your thesis at the end? You can, because you understand the rule you’re breaking.

The Bottom Line: Don’t scoff at the 5-paragraph essay. Master it. Own it. Use it to build unshakable confidence in your ability to structure an argument. Then, when you’re ready, you’ll have the foundation to soar beyond it.

Your Turn to Practice:

Let’s build an essay together. Use the prompt below:

Prompt: “Should school uniforms be mandatory?”

In the comments:

- Draft a thesis statement following the formula: “[Your position] because of [Reason 1], [Reason 2], and [Reason 3].”

- Write one complete T.E.E.A. body paragraph for one of your reasons.

I’ll provide feedback on your structure and analysis. Let’s see your essay skills in action!